Developing and Exercising Strategic Influence

In this series of articles on Strategic Leadership, I have discussed strategic leadership in general and have also explored the nature of strategic thinking. I then moved on to a consideration of strategic acting – or execution. The aspect of Strategic Leadership that we are currently exploring is that of Strategic Influencing – the formation and nurturing of strategic relationships over the long term. In this article, I will focus specifically on building your network.

In his fascinating book, The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell tells the story of Paul Revere and William Dawes, who both set out from Boston on the night of 18th April 1775 to sound the alarm that the Revolutionary War had begun, and to raise an army. Revere rode north, while Dawes rode south. Although they rode through towns that were demographically similar, and although they came from similar social and educational backgrounds, only Revere raised an army and became famous, while Dawes remains obscure to this day.

The critical difference between these two men lay in the network each man had cultivated over time. Paul Revere had a huge network of disparate and equally well-connected people, while Dawes had not managed to cultivate something similar, and so didn’t know who to speak to when he got to each town. Revere is what is known as an information broker – someone who plays a vital role in a social network because he knows lots of different and dissimilar people and connects them to each other.

Powerful networks offer three particular advantages to their members: firstly they give their members access to private information from personal contacts – information that is not generally available; secondly, they give their members access to diverse skills and competencies, and create the opportunity for generating lots of exceptional ideas, and developing more comprehensive, innovative and objective views of issues. The third advantage of a powerful network is that it confers tremendous power on its information brokers – in today’s flatter organisations, no longer is power vested merely by virtue of one’s rank in the organisation; it is vested in those individuals who have a wealth of ties with trustworthy and informative people.

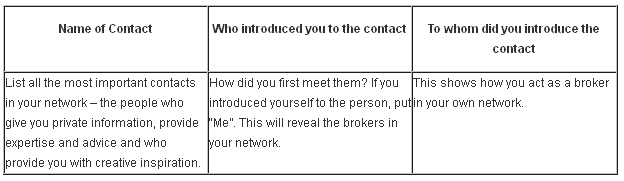

In their article “How to Build Your Network” in the December 2005 volume of the Harvard Business Review, Brian Uzzi and Shannon Dunlap suggest that in order to understand your network, you should map it using the following headings:

In his fascinating book, The Tipping Point, Malcolm Gladwell tells the story of Paul Revere and William Dawes, who both set out from Boston on the night of 18th April 1775 to sound the alarm that the Revolutionary War had begun, and to raise an army. Revere rode north, while Dawes rode south. Although they rode through towns that were demographically similar, and although they came from similar social and educational backgrounds, only Revere raised an army and became famous, while Dawes remains obscure to this day.

The critical difference between these two men lay in the network each man had cultivated over time. Paul Revere had a huge network of disparate and equally well-connected people, while Dawes had not managed to cultivate something similar, and so didn’t know who to speak to when he got to each town. Revere is what is known as an information broker – someone who plays a vital role in a social network because he knows lots of different and dissimilar people and connects them to each other.

Powerful networks offer three particular advantages to their members: firstly they give their members access to private information from personal contacts – information that is not generally available; secondly, they give their members access to diverse skills and competencies, and create the opportunity for generating lots of exceptional ideas, and developing more comprehensive, innovative and objective views of issues. The third advantage of a powerful network is that it confers tremendous power on its information brokers – in today’s flatter organisations, no longer is power vested merely by virtue of one’s rank in the organisation; it is vested in those individuals who have a wealth of ties with trustworthy and informative people.

In their article “How to Build Your Network” in the December 2005 volume of the Harvard Business Review, Brian Uzzi and Shannon Dunlap suggest that in order to understand your network, you should map it using the following headings:

If you have introduced yourself to more than 65% of your contacts, you may well be using the self-similarity principle to build your network – and that may mean that it is too inbred. You may also find that your network is populated with people you spend most of your time with, such as colleagues – the proximity principle. When self-similarity and proximity are the principles by which we build our networks, we create what Uzzi and Dunlap call “echo chambers” – all you hear is the voices of people who have similar experiences to you, think similarly to you, and see the world through the same lens you do, and this results in a dearth of diversity.

To enrich your network, you want to bring into it people who see things differently, think about things differently and who can stretch and improve your thinking – people who are dissimilar to you. To do this, one needs to move away from the self-similarity and proximity principles and favour a “shared activities principle”. Executives who participate in sports teams, community projects, voluntary associations, interdepartmental projects and charitable organisations where something is at stake, where passions are ignited and success depends on interdependence and cooperation, are more likely to have the kind of networks that Paul Revere had. Shared activities bring together different people with different experience, interests and ideas around a common project, and often eliminate the interference of rank. In these shared activities, people get to know people dissimilar from themselves in circumstances in which successes can be celebrated and failures shared. The usual patterns of interaction are also changed, allowing people to break out of their prescribed business roles of CEO, middle manager, IT boffin or Chairman and stand out from the crowd.

Returning to your diagnosis of your network … look at the people who are listed multiple times in the middle column – your brokers. What activities bring you into contact with them? How can you further develop these ties? Which of them are well-connected despite not being in positions of formal authority? Do they know how valuable they are to you and how you appreciate them? Who else could they connect you with, and how might you make that happen?

If you can build your networks with trust, diversity and brokerage you can raise your level of information from what you know to who you know – and by extension to who knows you.

In the next article, I will explore the kinds of relationships that are built by those who are really effective in the area of strategic influence.

Recommended Reads

If you are interested in reading more about networking we recommend:

“Becoming a Strategic Leader” by Richard L. Hughes and Katherine Colarelli Beatty (ISBN 0-7879-6867-6).

“Masters of Networking” by Ivan R. Misner, Don Morgan

The Networking Survival Guide: Get the Success You Want By Tapping Into the People You Know by Diane Darling

To enrich your network, you want to bring into it people who see things differently, think about things differently and who can stretch and improve your thinking – people who are dissimilar to you. To do this, one needs to move away from the self-similarity and proximity principles and favour a “shared activities principle”. Executives who participate in sports teams, community projects, voluntary associations, interdepartmental projects and charitable organisations where something is at stake, where passions are ignited and success depends on interdependence and cooperation, are more likely to have the kind of networks that Paul Revere had. Shared activities bring together different people with different experience, interests and ideas around a common project, and often eliminate the interference of rank. In these shared activities, people get to know people dissimilar from themselves in circumstances in which successes can be celebrated and failures shared. The usual patterns of interaction are also changed, allowing people to break out of their prescribed business roles of CEO, middle manager, IT boffin or Chairman and stand out from the crowd.

Returning to your diagnosis of your network … look at the people who are listed multiple times in the middle column – your brokers. What activities bring you into contact with them? How can you further develop these ties? Which of them are well-connected despite not being in positions of formal authority? Do they know how valuable they are to you and how you appreciate them? Who else could they connect you with, and how might you make that happen?

If you can build your networks with trust, diversity and brokerage you can raise your level of information from what you know to who you know – and by extension to who knows you.

In the next article, I will explore the kinds of relationships that are built by those who are really effective in the area of strategic influence.

Recommended Reads

If you are interested in reading more about networking we recommend:

“Becoming a Strategic Leader” by Richard L. Hughes and Katherine Colarelli Beatty (ISBN 0-7879-6867-6).

“Masters of Networking” by Ivan R. Misner, Don Morgan

The Networking Survival Guide: Get the Success You Want By Tapping Into the People You Know by Diane Darling